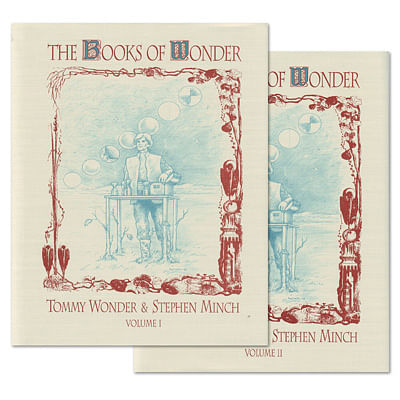

The Books Of Wonder Volumes One And Two by Tommy Wonder and Stephen Minch

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii June, 1996)

Tommy Wonder—inventor, builder, lecturer, widely regarded as one of the world's finest

all-around magicians, well-deserved (!) winner of FISM awards in both close-up and

stage magic categories—has given the world of conjuring what I believe to be among the

very greatest books of this, or perhaps even the next, century. It's difficult to imagine a

more extraordinary book than this being produced in our lifetimes.

These two volumes total close to 700 pages, containing between them a total of 56

technical entries (routines, tricks and/or sleights), half in each volume, amidst 34 essays

and articles in the first volume and 22 in the second, covering a range of subjects from

technique and craft, through misdirection and performance, on to art and philosophy.

There is close-up magic with cards, coins, cigarettes, cups and balls and more; there is

manipulative magic, children's magic, parlor, platform and stage magic. There are

sleight-of-hand and mechanical methods, each type as mind bogglingly original as the

other.

The first volume, following an introduction by Max Maven, is divided into five sections:

Attention Getting Devices is concerned with misdirection and related subjects; Travel

Tales of Mr. Pip includes eleven card items (three sleights and the balance being

routines); The Tamed Card, a Wild Card routine with associated essays; Presentations in

Silver, a section on coin magic; and finally, Group Encounters, including six routines for

children, parlor or small platform performance. The second volume parallels the first in

this general organizational scheme; and it is, I must add, a sophisticated and effective

scheme at that. Following an introduction by Eugene Burger, here the reader will again

find five chapters or sections, including: In the Trenches, a section of general close-up

magic; Acetabula et Calculi, concerning the cups and balls; Finger Sprints, containing

manipulative stage magic; Department of Utilities, addressing utility devices; and

finally, Mechanical Marvels, concerning apparatus magic.

Some readers may be familiar with portions of the contents via Mr. Wonder's distinctive

lecture or other previously published material, the most significant shares of which were

included in two sets of lecture notes: Jos Bema's Original Magic From Holland (1976),

and Wonder Material (1983). Another block of material was contributed, over a period

of several years, to Fred Robinson's highly regarded journal, Pabular. Items have also

appeared in journals including Linking Ring, Magic and Genii , and in collections such

as The New York Magic Symposium Collection Volume Five (1986) and the 1990 collection, Spectacle, both by Stephen Minch. All of this material reappears in the

volumes at hand, entirely rewritten and newly illustrated. Regrettably, these texts lack a

complete accounting of Mr. Wonder's published record. Notable amid that record is the

1983 manuscript, Tommy Wonder Entertains, subtitled Three Novel Routines based on

the Cups and Balls by Jos Bema, written by Gene Matsuura, which included a superb

description of the Two-cup routine, along with two excellent additional items. The Two-

Cup routine has been redescribed for these newly released books; the Matsuura work

remains the only published source for the two remaining routines.

One of the most impressive elements of these books is the organization of the material;

there is a symmetry and balance both between and within the two volumes, and a

deceptively easy relationship between the technical and theoretical material throughout.

Although the two volumes can be purchased independently, I cannot imagine buying

only one. This is a single unified work, reflecting a totality of one artist's vision, and

simply must be experienced as such.

The illustrations by Kelly Lyles are serviceable, although frankly not quite up the

standard of the rest of the production elements; admittedly there are some unusually

demanding aspects to the graphic challenges of this book, such that would have no

doubt tested any competent illustrator, but on occasion Ms. Lyles remains only barely

up to the task. A draftsman-like precision would have been useful in the case of some of

the most mechanically technical material, and the portraits of the author are

distractingly unflattering. Nevertheless, the publisher is at least generous in most cases

with the quantity of illustrations, and that is greatly appreciated.

And so—imagine a Wild Card routine with a unique and entertaining presentational plot

that actually justifies the effect with a meaningful kind of logic; imagine a Wild Card

routine designed for walk-around conditions, without a performing surface, where

virtually all the cards are dealt into the spectator's hands; imagine a Wild Card routine

which recycles itself. If in the first performance you change all Two's of Clubs into Kings

of Hearts, were a curious spectator to follow you to your next performance, he would see

you bring out a packet of Kings of Hearts and change them into yet another card

entirely, with which you would then begin your third performance before cycling back to

the original deuces. Try and imagine that, but don't hurt yourself—it's called The Tamed

Card, and you'll find it in Volume One, accompanied by no less than ten relevant and

indispensable essays.

The crowning technical entry of the first volume is an amazing and elegant handling for

Oswald Williams' Burglar Trick, in which the magician's money, finger ring, and wrist

watch vanish, while a tale is told of a robbery, only to magically return to the performer's

wallet, finger, and wrist. A number of versions of this trick have recently been seen both

in performance and on the dealer's shelves, but let me assure you that none comes even

remotely close to the beauty and deceptiveness of Mr. Wonder's; when I first witnessed

it—almost a decade ago—I was so badly fooled that it was the first entry I turned to

when I pulled the galley pages from the package just a few weeks ago. Be forewarned

that not every reader will have the wherewithal to construct the necessary props for both this and a number of other mechanical items in these books, but should you wish to do,

so the information is all here in careful and caring detail.

The first of the book's five chapters, entitled "Getting the Mis Out of Misdirection,"

contains three articles of extraordinarily clear and practicable thinking about

misdirection. Some of the concepts presented here are remarkably fresh and original;

while experienced performers may recognize some of these ideas, one of the great

services that discerning critical thinkers like Mr. Wonder render is that they help to

provide the rest of us with tools with which we can better utilize sometimes disparate

fragments of information we might already possess. In "Attention Getting Devices," the

author states that "Your goal is to make everyone believe that they didn't miss a thing,

yet miracles happened." He then goes on to provide a number of extremely useful tools

for achieving this obviously desirous end. Mr. Wonder is ruthless in his demands of both

himself and his work; he is also extremely eclectic in his choice of weapons with which

to achieve these goals. In the course of these books, you will be introduced to a panoply

of tools—psychological, manipulative and mechanical—to insure that your methods

remain invisible and your deceptions absolute, and this array will eventually be

summarized in a thought-provoking essay late in the second volume titled "The Three

Pillars."

Throughout, Mr. Wonder shares his thinking about what is good and bad about magic,

and how to make it better. His background, training and experience in theatrical arts

leads him to comment that "When people begin to identify with you, to recognize the

feelings you are feeling, they stop simply watching the magic and begin to experience it.

This is what makes magic interesting and something worth paying to see." And Mr.

Wonder's ideas of "good" and "better" are ambitious and sophisticated. In an essay

entitled "High and Low," he points out the pitfalls in too often aiming our work at or

near the lowest common denominators of entertainment and audience. "To be so direct

in our work that we lose the culturally educated, more sensitive audiences is a loss—as

much of a loss as losing the less refined audiences. Since, for most of us, our market

encompasses all levels of cultural educations, it would better serve us if we could please

all levels." Hence we are asked to consider not only the artistic implications of bringing a

higher level of cultural, intellectual and artistic sophistication to our work, but the

commercial ramifications as well. Mr. Wonder is frank in pointing out what he perceives

to be the limitations of magic: "...the times are gone when people automatically awarded

respect for doing something they can't. For one to win respect for a skill today, it must

either do something for or mean something to other people." Mr. Wonder's prescription

for future success? "The whole face of magic would change completely if we never again

did things without having a presentational reason. The majority of magic today is

vacuous non-sense. .... If we wish to be seen as a mature performing art, we must stop

being shallow and trivial ourselves. Ensuring that there are always reasons for the

effects we perform is a small step but an essential one in elevating magic to a level

worthy of respect." And, oh yes, one more thing: "To begin with, we should immediately

stop accepting such ideas as 'The audience doesn't notice all those nuances,' for in

virtually every audience there are those who do."

How do we make our performances more powerful and compelling for the public we

wish to entertain and affect? In an essay on acting (and what some might call method

acting) for magicians, he tells us that "Acting is not making faces; it is thinking and

feeling what you think. This practice controls the body's expression of emotion far better

than can ever be achieved by conscious control.... Thinking is necessary, thinking plus

belief. Without these things there can be no acting." If you doubt this, ask yourself—or

better yet, ask an objective layperson—how convincing was the acting the last time you

saw a magician discover that he has "mistakenly" burned up the spectator's bill,

"accidentally" forgotten to locate one selected card among many, or supposedly riveted

the audience with a portrait of love's fiery passions playing across his face; more often

than not the only mistake is the magician's in believing he has convincingly acted any of

these roles. Mr. Wonder adds further, in an essay on "Conflict and Emotion," that

"Emotion is interesting, and in theater it is ultimately the only thing that counts. The

rest is dull, extremely dull. ... Most magic is extremely dull."

Tommy Wonder's Two-Cup Routine hardly falls into that category, and it will be found

in Volume Two in all its glory. This achievement is perhaps Mr. Wonder's most famous

single creation, described here in its entirety. The routine is magic of the purest sort:

Two and a half minutes of effect, plot, and character, with a minimum of verbiage and a

great deal of action. For those who came in late: Two cups are withdrawn from a cloth

drawstring bag, which is set aside on the table; the drawstring terminates in a large

pompon. The routine which ensues is performed with two rather sizeable pompon-like

balls, and consists of a number of surprising and original phases, as in the opening

segment when one ball placed beneath each cup is then magically and visibly withdrawn

through the tops of the inverted cups. In the course of events, the pompon magically

appears under one of the cups, having mysteriously detached itself from the tabled bag.

Somewhat nonplussed by these occurrences, the magician reattaches the perverse

pompon to the bag's drawstring. Continuing with the routine, the magician eventually

causes one of the balls to vanish and appear under a cup on the spectator's own hand,

another unique effect in the annals of cups and balls magic. Ultimately, the performer

lifts one of the cups to discover the drawstring pompon beneath it yet again! Turning to

locate the previously tabled bag, the magician discovers that it is now missing. In

curiosity mixed with trepidation, the performer lifts the second cup—within which is

found the scrunched up cloth bag!

"If you don't enjoy this work, if you don't have the time for it or you just

don't want to expend the necessary effort, but you do delight in watching

magic, reading about it, meeting other magicians, toying with the ingenious

props and secrets—then I think you should realize that you are not an

amateur, let alone a professional. You are a FAN of magic.... Fans do not do

shows. If you want to do shows, then be an amateur and put in the work

required." —Tommy Wonder, The Books of Wonder

That extraordinary climax is misdirective magic of the highest order; that is, magic in

which the audience seems to superficially "understand" the method—the magician must

sneak the items into the cups without the audience noticing—and yet is increasingly

astounded by the magician's repeated success. This is, in my estimation, one of the highest forms of conjuring, for it requires an absolute mastery of misdirection; it is also

the one kind of magic wherein repetition serves to continuously enhance rather than

detract from the impact of the effect, as in Heba Haba Al Andrucci's Card Under Object,

or Albert Goshman's coins and salt and pepper shakers.

While I wouldn't recommend anyone try to duplicate outright such a signature piece,

this is an inspiring piece of work, the study of which, for its own sake, will yield

countless insights. The changes Mr. Wonder has wrought go far beyond the obvious

ones of the final loads: the routine's unprecedented climax was discovered in the course

of the creator's search for a practical solution to the management problem of final loads

weighing down bulging pockets (the solution: the loads double as the carrying case, and

you just leave them out in the open); consider also that he never once goes to his

pockets, even at the completion of the routine, and thereby eliminates their use as any

possible explanation for the audience. This is a work of purity and genius, and nothing

less.

One of the most bountiful sections in either of these texts is the chapter on utility

devices. Mr. Wonder makes some marvelous contributions to established devices such

as the tails and belly servantes, geared toward improving their reliability and efficiency.

He also discusses the so-called pendulum principle, an idea exploited previously by the

regrettably all but unknown performer Jan, along with John Cornelius and others. And

he contributes a simply extraordinary addition to the Jack Miller holdout that should

revolutionize its use for serious practitioners. In brief, Mr. Wonder has created a device

he calls the "Frozen Lock," which maintains the pull up and out of view and reach when

not in use, and releases it to bring it down in reach for use, all at will and—and think

about this carefully—without any moving parts. The implications are boundless for the

dedicated and inventive professional, and if you don't think so, then you've been very

badly fooled indeed by Mr. Wonder's beautiful and deceptive stage act.

An effect that Mr. Wonder knows a great deal about is the Zombie, which he discusses in

Volume Two in both a technical contribution and an accompanying essay. The author

has a great deal to say about this timeless, oftabused and ill-used effect, and for good

reason; he has obviously invested a great deal of effort in the subject, as evidenced not

only by his thoughts here, but by his breathtakingly magical floating cage from his

aforementioned stage act; a work which is, I will add, one of the most elegantly plotted

and richly conceived silent acts I have ever seen. Mr. Wonder has contributed a number

of significant technical improvements to the Zombie principle, some of which he

describes in the text. Other elements will remain restricted to those who make the

modest but no doubt wise investment in his commercially-released version, the advance

advertisements for which began to run several months ago. In the interim you can read

some of Mr. Wonder's original ideas, and much of the thinking and theory behind them,

in Volume Two. A sample of the latter: "With many tricks people can cheat their

audiences into thinking they've studied their art, because their lack of artistry and skill is

protected by the secret! Not so with Zombie. Zombie ruthlessly filters out the bad

magicians and reveals them to all. Zombie proves that magic cannot be achieved without

thought... Zombie is to magic what magic is to the other arts: It is often held in very low

esteem, but it can be one of the finest."

While I simply cannot address the entirety of these books—the myriads of technical

entries, or the scope of the theoretical material—in Volume One they include: a multi-

phase coin routine which climaxes with the startling appearance of one of the coins in

the performer's eye, monocle-fashion; a manipulative stage routine with plot and

reason, wherein cards and their case cavort seemingly at their own will, transforming

one into the other, and back again, and transposing places, too; a billiard ball routine

which introduces an entirely new principle to the subject, namely an unusual change of

shape of the "balls;" and a series of wacky and intensely visual effects with playing cards

in which card boxes shrink, pips are shaken from one end of a deck to the other, and

poker-sized cards are visibly forced into a miniature case! In Volume Two, Mr. Wonder's

discussion of the Vanishing Birdcage and the locking take-up reel will, to the expert and

skillful user of apparatus—admittedly an increasingly rare breed of conjuror—be worth

far more than the entire purchase price of these books. And three complete versions of

the watch in Nest of Boxes serve to bring the mechanical material to a mindblowing

climax; here we find ourselves virtually plunged into the author's mind as we join him

on the voyage of a fantastic search for the ultimate effect, and its requisite ultimate

methodology.

"If, in a magic organization, brotherhood is elevated above the development

of quality magic, magic will suffer and the magic organization will have

become an anti-magic organization!"—Tommy Wonder, The Books of Wonder

Some of Mr. Wonder's cogent commentary about the anthropology and sociology of

magic may well raise some hackles, but is possible that the essay that may cause the

greatest controversy among serious practitioners will be the one addressing the Too

Perfect Theory. While there has been much discussion about this subject since Rick

Johnsson's influential 1971 essay in Hierophant [page 454 ], surprisingly little has

appeared in print. Although this is certainly an oversimplification, in my personal

experience the theory's most vocal critics are frequently non-performers, while fulltime

entertainers tend to support its basic premise, albeit with reservations in some cases;

admittedly there are plenty of exceptions on both sides of the argument to go around. In

contrast, Mr. Wonder comes down firmly against the theory—or, at least, claims to.

"Claims to," because I believe we can find examples elsewhere in his work where one

might be inclined to suspect him of adhering to the tenets of the theory. Despite the fact

that he makes some vehemently negative claims about the theory, declaring it defeatist

and emphatically insisting that it must invariably lead to inferior magic, his examples

appear isolated and unconvincing to me. In Mr. Wonder's superb version of the Kaps

Card in Ringbox, for example, he might easily repeat the mistakes of some others,

namely to give the box directly to the spectator at the start of the effect. Of course, if you

do this, some segment of the audience will, because the effect is too perfect for the

method to support, thereby successfully puzzle out the method. I can only surmise that

Mr. Wonder avoids such a flawed approach because he realizes this hazard, and instead,

following the path of the Too Perfect Theory, "weakens" the effect a tad by leaving the

box out on the table. Of course, in actuality he has not weakened the effect, he has

strengthened it; what he has done is softened the proof—and wisely.

Similarly, in a clever effect with miniature slates described in Volume Two, Mr. Wonder

explains that, "When I first developed this trick, I showed all four sides of the slates

blank at the start, then made the four messages appear. But experience proved that this

was not as deceptive as when I failed to show one side, deliberately creating suspicion

and a false solution that I later knocked over. Perhaps showing all sides blank before

producing the messages was just too much, leaving the audience thinking that the slates

must be mechanical, which unfortunately they are. However, if a false solution is set up

in the beginning, then is suddenly knocked over, it frustrates correct analysis and

produces the magic effect we desire." Perhaps showing all sides blank before producing

the messages was just too perfect, and by making the effect a bit less perfect, a more

effective illusion was achieved. I admire and respect Mr. Wonder's goals, and in fact

appreciate his reservations about the theory's risks, but I would not blame the theory for

those who apply it poorly.

But whether I agree or disagree with Mr. Wonder on this or any other subject is quite

beside the point; the point here as elsewhere is that we have been invited into dialogue,

between the author's ideas and our own, between our own and those of our peers, and

we have been encouraged into a discussion at a high level; frankly, at an adult level. In

fact, what repeatedly struck me as I read these books is that these are truly adult books,

among the most mature conjuring texts I have ever read. They are books for people

whose interests and outlook extend to a universe of ideas far beyond the culturally

claustrophobic borders of magic; who are informed in their perspective, cosmopolitan in

their world view and mature in their experience. These are, in sum, books for grown-

ups— and in magic that seems to me a rarity, even more so now that I have read these

new works. These are grand books, where every page seems to brim and seethe with a

riot of ideas and inspirations.

The Books of Wonder seem the perfect arrival for fin de siècle conjuring; there is a

lurking sense of change in the wind these days, of some coming to an end of sorts, of

impending catastrophe even, of important issues at stake that we must consider if we

are to rescue our art from on-line trivializers and video marketeers and television

exploiters. All of that is reflected in these books, and beyond their tough love messages

there is also something of birth, of spring, of newness and joy in these pages. These

books contain more than merely state-of-the-art technology, or even state-of-the-art

thinking; they comprise an apt report of the state of our art today. There are truths to be

found in the pages of this book; truths about art, about life, and— Wonder of Wonders—

about magic.